Self-sabotage or self-protection?

And Why It Matters to Use the Term ‘Self-Protection.’

The term ‘self-sabotage’ is widely used, and the word often carries a negative connotation. Hearing the term, or ‘accusing’ yourself of it, can trigger an inner reaction that wants to correct, feels ashamed, or becomes self-critical, believing you simply need to try harder. But what if the behavior we label as self-sabotage is actually a protective mechanism? What if there is a part of you that withdraws, procrastinates, or blocks—not because it wants to thwart you, but because it wants to shield you from something? From overstimulation, failure, rejection, or pain.

In this article, my goal is not to provide an exhaustive explanation of the Internal Family Systems (IFS) therapy model by Dr. Richard Schwartz. However, I do want to offer a glimpse into this philosophy, in the hope that you might better understand the foundation of my vision. According to the IFS model, every human psyche consists of different ‘parts.’ This is the natural structure of our psyche. These parts represent aspects of our personality and experiences. In daily life, we constantly switch between these parts, often without even realizing it. For most people, this process is fast, fluid, and largely unconscious.

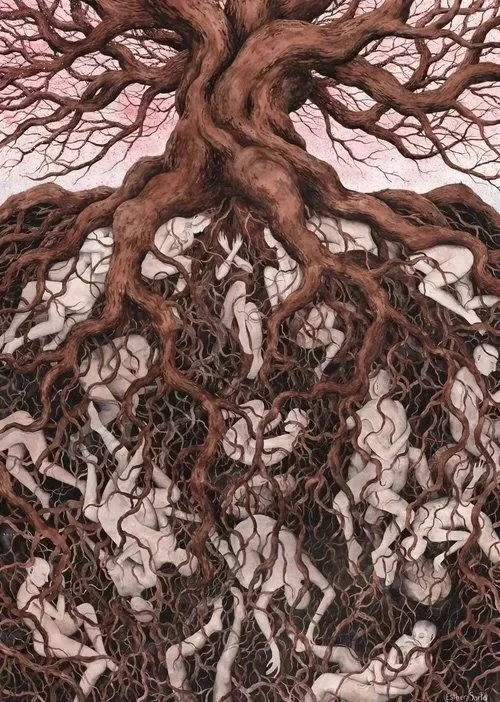

Many people recognize this inner dynamic as soon as they are given the language for it: one side wants to rest, while the other wants to push through. One part is enthusiastic, while another feels fear. IFS assumes that we are all born with these parts; they are naturally part of being human. Therefore, they are not created by trauma. However, trauma—much like chronic stress, rejection, cultural conditioning, or insecure attachment—influences the development and functioning of certain parts. They may then take on protective roles to help us survive, maintain control, or ensure we adapt in hopes of belonging. Their intention is always positive, no matter how clumsy, painful, or confusing the resulting behavior may sometimes feel.

Repeated and intense trauma often creates stronger divisions between these parts (such as amnesia). But the parts themselves, with their emotions, beliefs, and behaviors, are just as valid as anyone else's. This perspective helps us to avoid pathologizing parts and instead recognize them as natural reactions to what we have endured. They are not fractures, but protective mechanisms—whether intense or subtle—that once served a clear purpose.

When we exhibit behavior often labeled as self-sabotage, it is not because we consciously want to work against ourselves. On the contrary: our system is trying to protect us. Our inner parts once learned that certain behaviors could shield us from pain, rejection, or failure. What looks like self-undermining is, in reality, often an attempt by a part of us to keep us emotionally safe, whether the threat is real or imagined.

That is why I prefer the term self-protection. When we reframe our behavior in this light, a sense of compassion emerges. We begin to see that these parts are not working against us, but are trying to fulfill a protective function. By recognizing and understanding these parts, we can approach ourselves with more kindness, curiosity, and clarity.

The Power of Language in Self-Understanding

The way we speak about and to ourselves matters. At the core of who we are lies what the IFS model calls the ‘Self.’ This ‘Self’ is described as a calm, curious, peaceful, compassionate, creative, and centered state of being that reflects our true essence. This Self exists in every human being, is indestructible, and inherently knows how to heal. Yet, this Self can easily become overshadowed by various parts within us that have been shaped by past experiences.

What makes it challenging to view your psyche as a collection of parts is that they usually express themselves through feelings. Because of this, we don't experience them as distinct parts, but simply as emotions—especially when such a part has become alienated from the Self. Healing occurs through a compassionate connection between the parts and the Self—a relationship that offers enough safety and trust to ‘release’ parts, allowing them to let go of the legacy of the past (Fisher, 2009).

Learning to recognize and distinguish when different parts of ourselves come to the forefront is a valuable skill. Once you recognize them, you can enter into a dialogue with them to learn about their intentions and needs.

Different Perspectives On The ‘Self’

In IFS, this core state is called the ‘Self,’ but other approaches use different terminology. Some link it to the prefrontal cortex (research shows that when this brain region is not blocked, we have access to the Self – Janina Fisher, PhD, 2023). Others call it consciousness, an inner sense of wholeness, or the ‘healthy adult’ (as seen in Schema Therapy).

Consciousness is often viewed as the broader state of awareness of our thoughts, emotions, and experiences, while ‘awareness’ describes the focused attention we give to something in the present moment. In some approaches, such as iRest, the Self is described as an ‘inner resource’—a safe place within the body where we can experience deep peace, security, and well-being.

Ultimately, the precise terminology is less important than the ability to recognize and embody this state. It is not an abstract idea, but a deeply felt somatic experience. There are many paths to reaching this state; what matters is finding an approach that resonates with you.

For years, I practiced various forms of meditation and Yoga Nidra before I encountered IFS. Looking back, I see that those practices specifically helped me connect with the Self. But accessing this state doesn't have to be complicated—sometimes a simple exercise, like the one described below, is just as powerful.

My Personal Journey With IFS And Body-Oriented Work

I’d like to share something about my own experience with IFS. To process trauma and the lingering traces it left in my system, I spent a significant amount of time in therapy as a client. During this time, IFS and body-oriented work played a crucial role in my process. I can sincerely say this was a turning point in my journey.

What I discovered, especially through bodywork, is that physical exercises alone don't always reach the core—for instance, when a ‘part’ is in the foreground and the connection with the ‘Self’ has receded. Sometimes movement helps me regulate and reconnect with the Self. However, there are also moments when movement activates another part—one that tends to want to ‘resolve’ or ‘fix’ what I’m feeling, rather than allowing what the other part actually wants to show me. Even then, a protector is at work—trying to shield another part.

In those moments, what helps me most is a layered approach. If movement alone isn't enough, I choose another way to connect with myself: I speak softly and lovingly to myself (either out loud or in my mind), I wrap my arms around myself, or I slowly and gently stroke my skin. To return to the here and now and activate my prefrontal cortex, I rub my hands together, look around slowly, and name what I see. By engaging my senses, I return to the moment. Smelling something, like an essential oil or a warm cup of herbal tea, can also be helpful.

This way of listening with compassion and allowing what is there helps me reconnect with my Self. But this didn't happen overnight; it requires practice to learn to recognize these dynamics within myself. Sometimes movement is enough. At other times, it’s necessary to pause, sit with myself, and engage in an inner dialogue. And sometimes, the part that has taken the lead simply needs its needs acknowledged—whether that’s offering reassurance or seeking connection with a safe person, such as a friend.

As a holistic therapist, I consciously chose not to dive too deep into the theory of IFS at first. I wanted to embody it first, without my mind getting in the way. But after experiencing the power of this method myself, I began to study the books of Richard Schwartz (the founder of IFS) and completed a course by Janina Fisher PhD, psychotherapist and trauma expert.

The Connection Between Parts And The Nervous System

It is important to realize that our various parts are closely linked to specific states of our nervous system—fight, flight, freeze, or fawn—and vice versa.

According to the Polyvagal Theory, developed by Dr. Stephen Porges, our nervous system constantly responds to signals of safety or threat. This causes us to shift between states of safety and connection, or states of stress and survival. These states influence how we react, how we view ourselves, and which parts become active.

Sometimes, a single sentence from someone is enough to activate a certain part, including its corresponding nervous system state. They are intertwined: when a part is triggered, the associated emotional and physical reactions come with it.

This is another reason why language matters. The word ‘self-sabotage’ often sounds accusatory or judgmental and can reinforce our sense of inner conflict. ‘Self-protection,’ on the other hand, invites curiosity and understanding, allowing us to collaborate with our parts instead of fighting against them.

Notice how your body reacts to words. Do you feel an opening or a constriction at the word 'self-sabotage'? And what do you notice when you use the term 'self-protection'?

The key to recognizing parts is using the ‘language of parts.’ In other words, try to translate your inner narrative from ‘I’ to ‘a part of me.’ For example: “A part of me feels shame,” “A part of me thinks it was my fault,” or “A part of me feels anxious.”

By labeling the symptoms you experience as parts, you stay connected to your prefrontal cortex because this practice promotes curiosity and focus. Furthermore, naming tension as a part makes emotions feel less overwhelming (Fisher, 2023).

A Gentle Exercise For Self-Compassion And Awareness

To explore this concept in a personal way, you can try the exercise below. This practice supports you in engaging in an inner dialogue, fostering understanding and self-compassion. Instead of labeling parts of ourselves as "problem behavior," we learn to see them as protective allies—even when they seem to act against our own best interests.

A Practice

Prepare your space: Start by choosing a place where you feel comfortable and safe, and where you can remain undisturbed for a few minutes. You might want to move your body a little before sitting down, preferably in an upright and relaxed position.

Orient yourself: Look around while moving your head and eyes as slowly as possible, and mentally name a few things you see.

Settle in: You can close your eyes or keep them open—it’s always good to alternate between the two.

Listen: Begin to listen to the sounds around you. Sounds inside and outside the room. You don’t have to actively search for sounds; let them come to you.

Feel: You might feel the air on your skin, the weight of your body touching the surface beneath you, or the sensation of gravity.

Scan: Slowly travel with your attention through your body and feel where it makes contact with the ground or other surfaces. Notice how your body connects with its surroundings, and how the surroundings touch you back. Let your attention rest in this moment for a few minutes.

Observe: Now, observe your body. Perhaps there is a spot that calls for your attention because of a specific sensation or emotion. You might hear voices or notice thoughts in your head. Try to recognize and distinguish them as parts of yourself, rather than as one integrated "I."

Softening resistance: If you hear a voice of resistance or criticism, kindly ask if it can step back for a moment.

Connect: Spend a moment with this part of yourself and feel its presence. Can you enter into a conversation with this part? You can try asking (one of) the following questions, either in words or through touch:

Why are you here?

What are you trying to protect me from right now?

What do you want me to know?

What do you need?

How can I support you?

Listen: Wait and listen. Feel what happens within you as you make space for these parts. Do not be surprised if you encounter resistance; it is natural for protective parts to resist when questioned. If this happens, ask again what their role is, what they want to protect you from, and what message they have for you. Then, wait patiently.

Close with gratitude: End the exercise by expressing gratitude to this part of yourself. It is a piece of your humanity asking for your attention, care, and compassion.

Return: Finish by slowly looking around again and perceiving the space you are in. Name a few things you see. If it feels right, stretch gently and slowly rub your hands together while feeling your own skin.

By reframing self-sabotage as self-protection, we create space for a deeper and more compassionate way of understanding our own behavior. This shift allows us to heal and grow without the heavy weight of shame or judgment that often accompanies harsh labels.

I wish you an abundance of compassionate presence, both within yourself and in the world around you.

With warmth,

Iris